We're nowhere close to deep decarbonization with this plan

Contrary to celebratory headlines, the electric car revolution is not here, and it won't be here for decades.

In the near future, EVs in the US are about 60% less carbon intensive than their ICE counterparts. In countries with dirtier grids, that number is a lot less attractive - in China, for example, EVs are only roughly 37-45% cleaner over a lifetime of use.

Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF)

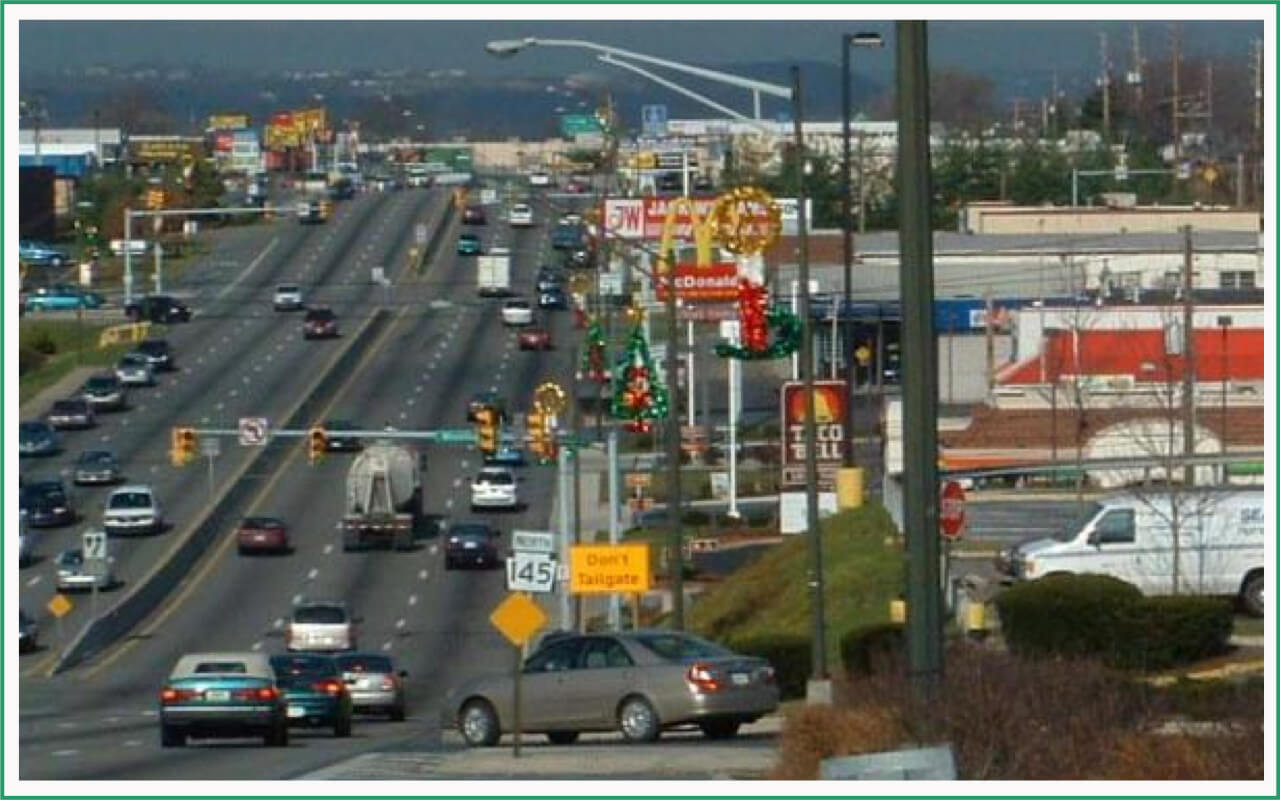

But the most critical challenge is just how long it will take to get these moderately better options into drivers' hands. First, EVs need to grow from the low single digit percentage of new vehicle sales they represent today - forecasts suggest it will take until after 2030 for them to reach 50% of new vehicle sales. Then, we need to wait for the overall pool of cars to turn over since people only buy a new car every few years - sometimes only once a decade! This slow replacement cycle is why projections suggest that the majority of cars will still be polluting ICE models well beyond 2040.

Source: WSJ

What's worse, trying to accelerate this glacial process is astronomically expensive. Biden's infrastructure bill plans to channel $174 billion dollars into electric vehicles. This is more than the GDP of Hungary or Qatar and another 162 countries. And what is this money really doing? The simple answer: making oversized electric vehicles cheaper so rich people will buy them. We're literally writing $7,500 checks to wealthy, largely white families buying Teslas and Hummer EVs as their second or third car. And lacking any real ideas, the latest proposal is simply to up that to $12,000 in the name of environmentalism with the hope that a larger swath of the upper-middle class will cash in.